By Nancy Sullivan, Our ‘Man’ in Papua New Guinea

There’s a Melanesian Spring blooming in Papua New Guinea, even if Spring doesn’t really exist in this country of rainy and yet more rainy seasons. The Internet came late to us, and even then, only the arrival of the Irish billionaire Denis O’Brien and his mobile phone empire—Digicel—could kick off our telecoms revolution. In the last five years or so, Digicel has completely transformed the social media landscape in Papua New Guinea. Now with wireless hotspots, smart phones and new phone masts popping up all over, remote villagers who have never left their plot of ground can call their cousins in town, contact their members of Parliament, search for the market prices of coffee, scroll through the daily paper, and receive group emails about Occupy Wall Street.

This country has more Cessnas than roads. It has one-fifith of the world’s languages. For the last two decades the primary schools have been struggling to get third graders to move from the lingua franca, Pidgin, into an English curriculum, with only marginal success. And now, SMS has made it all irrelevant. Digi-speak now exists somewhere between Pidgin syntax and English double-entendres, and it has jumped from mobile phones to emails to Gacebook and all kinds of PNG blogs today.

Under a Facebook discussion called ‘You know you’re in PNG when…’ there are typical Digispeak entries: ‘….wen u rush 2 Emergency n av 2 pay da hospital bills b4 anytin cn b done 2 treat da dying patient…’ and ‘you get strange calls in da middle of da nite wit da person on da other end saying, ‘mi laik kamap fone friend blo yu’..bara wes ya!, and my favourite: ‘when people say ” body bagarap but engine kick yet”’.

Inevitably, there have been drawbacks – every revolution has its dark side. Last year, at the Maprik Women’s Crisis Centre one of the counselors told me the story of an elderly village couple now considering divorce (unheard of!) It appears that the old man left his Digicel phone behind when he went to the garden and curious, the wife started pushing buttons. Eventually she found a woman’s voice telling her something about a message box. When her husband got home she threw the phone so violently at his head that he needed stitches.

Elsewhere, young girls are getting irritating ‘gas pia’ (gas fire—”shot in the dark”) calls from boys who never before have had such easy access. One of my own daughters was so consistently harassed by a strange young man she had to change her number.

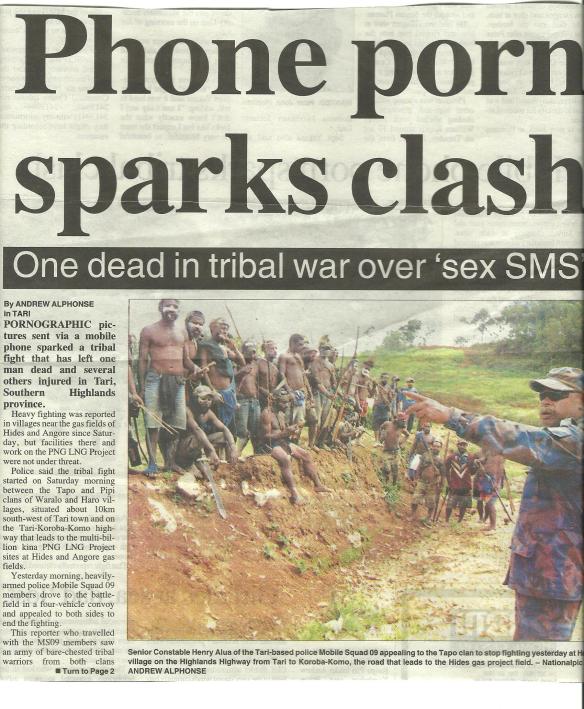

The Internet in your palm only compounds these problems. In remote parts of the country you carry an axe in one hand and a Blackberry in another. Last year when the US Tea Party photoshopped Barak Obama onto an African witchdoctor, it turned out the remote Huli wigmen of the Southern Highlands recognized the image of their traditional dress on a Smartphone download and called for their brethren in the capital city to stage a protest during Hilary Clinton’s visit. Apparently they were asking for a million kina (about £300,000) compensation for the abuse of their image.

But the biggest effect of all of this has been political. As of 1st September 2011, there are 54,180 Facebook members in PNG– 32,580 (60%) male, 21,240 (40%) female, and 360 of unstated gender. Most of these are young, urban, educated and loquacious. After decades of government corruption, criminal neglect of the villages, and a yawning gap between the grassroots and the new urban elite, this generation of Papua New Guineans online are not taking it sitting down. They blog, petition, group and poke all day long on Facebook, and it’s all very exciting.

Almost certainly this groundswell of populism played a part in this year’s coup of the old regime, installing a whole new raft of younger MPs in Parliament, at least four of whom have their own Facebook pages.

Recently the social media crowd really assembled to do some good. It started with a news report of domestic violence. December last year, one of the newspapers ran a story about a young mother, Joy Wartovo, who was in hospital with ghastly wounds from torture and beatings by her husband, Police Constable Simon Bernard. People were outraged, they wrote to the paper, but not surprisingly, the husband was never held accountable. This week, the same paper reported Joy’s return to the hospital, this time with even more horrible wounds. She had been burnt by a hot iron, a hammer had broken her fingers, and there were big burns and bruises all over her body. This time it wasn’t the newspaper but Facebook that lit up with outrage. Domestic violence is nothing new in PNG; this is a country where large dowries can make men feel entitled to do what they like to their wives. There is no such thing as marital rape, for example, and women commonly fight each other over male adultery.

For whatever reason the timing was right for this single incident to represent the hundreds (probably thousands) of women who attend aid posts every day after domestic violence in PNG. One very prominent Facebook page and activist blog called “ActNow!” is run by the young, smart and outspoken environmental lawyer, Effrey Daedemo, who immediately drafted a petition calling for the police to stop harbouring this monster, Steven Bernard. She called for everyone on Facebook and everyone subscribing to her web page to sign a petition and make change happen. Within a couple of hours, she had 500 signatures. Within 24 hours, she had 2000.

Yesterday it was delivered to the Chief of Police. More than 5000 have joined Effrey’s Facebook group in support, and 400 or so have sent individual emails to the Chief of Police. Not surprisingly, most of the politicians on Facebook have now joined the campaign. Today the papers (and Effrey’s web site http://www.actnowpng.org) reports that the Metropolitan Police Superintendent of Port Moresby is leading the hunt for this rogue policeman, and he admits that it was the public outcry that forced his hand.

Twenty years ago I was making some of the first music videos in this country, working with PNG popstars who have their own distinctive sound and musical history.

When they began to incorporate ‘foreign’ elements into their videos, like background dancers in short skirts (very rare in those days), the public outcry was immediate: people were shocked, even women sneered ‘whore!’ in letters to the editors, and the tribal cousin-brothers of two of these first young video dancers broke into their flat and attacked them. During this same period, I was driving around the capital listening to a national development symposium on the radio and a talk given by the male researcher and so-called ‘gender’ expert which unabashedly told all women in the audience that they would not experience so much violence if they just performed their wifely duties better. I almost crashed my car.

Now we have vast billboards of fresh young Melanesian women in short skirts, even swimsuits, advertising Digicel phones.

Then fifteen years ago, I was in a remote highland village listening to a foreign environmentalist talk about his dreams for the future of rural PNG. He sounded airy and idealistic, and talked about the most exotic things to these villagers. His dream, he said, was that these village farmers would someday have their own laptops and satellite internet, and so be able to bypass all these development middlemen, sell their crops online, buy their equipment online, communicate with emergency services online, and live the haute bourgeois farmer’s life they had always dreamed about.

Today, my God, this is happening.

Yes, I know, this PNG Spring may not yet be a new page for governance here. When a country ranks 154 out of 178 in the 2010 Transparency International Global Corruption Index, it’s hard to clean the system up overnight. But what the internet, social media and mobile telephone is doing is building a stronger civil society. And this cicil society is just not gonna take it anymore. It’s not yet a 99%-ers movement (perhaps more like a 5%). But it’s a civil society flexing its muscle, and trying to build a stronger political will for good governance and positive change.